The Inverted Yield Curve and Other Recession Indicators

The third quarter of 2019 was full of noise and lacking substance. There was a terrorist attack on oil facilities in Saudi Arabia, which affected the price of oil for about two weeks, and now oil is right back where it started. The U.S. dollar continued to grind higher and has now appreciated ~12.6% since its 2/16/2018 low. Manufacturing and trade continued to wane as the trade war drags on. The S&P 500® Index, NASDAQ and Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) were each up about 1% while small caps continued to lag. Gold went up ~10% and then gave half back. Central Banks around the globe continued lowering interest rates in the latest easing cycle like the many we have seen over the last ten years. Brexit languishes on…

We’ve covered these topics ad nauseum over the past year in our blogs and quarterly commentaries, as have many other market commentators and strategists. Therefore, to avoid repetition, we’ll largely refrain from rehashing our ongoing concerns and instead focus on new developments. In our opinion, there was one major newsworthy event this quarter: the inversion of the yield curve.

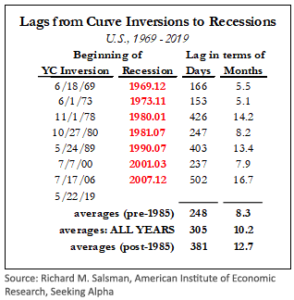

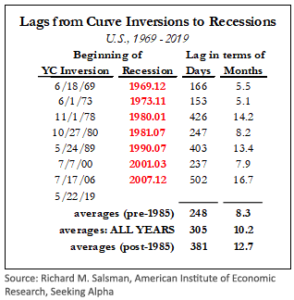

Historically, when the yield of the 10-year Treasury Bond has fallen below that of the 3-month Treasury Bill—a yield curve inversion—a recession has followed. From the beginning of 1969, up until the most recent recession which started in December of 2007, an inversion of the yield curve preceded all seven recessions. The yield curve first briefly inverted at the end of the first quarter of 2019. It inverted for a second time in May and has remained inverted since. At one point, as long rates plummeted during the third quarter, the yield of the 3-month Treasury Bill was 57 basis points higher than that of the 10-year Treasury Bond. While a yield curve inversion has been a solid indicator of a recession, it is imprecise at best. Historically, the time until a recession has varied between five and 16 months.

Historically, when the yield of the 10-year Treasury Bond has fallen below that of the 3-month Treasury Bill—a yield curve inversion—a recession has followed. From the beginning of 1969, up until the most recent recession which started in December of 2007, an inversion of the yield curve preceded all seven recessions. The yield curve first briefly inverted at the end of the first quarter of 2019. It inverted for a second time in May and has remained inverted since. At one point, as long rates plummeted during the third quarter, the yield of the 3-month Treasury Bill was 57 basis points higher than that of the 10-year Treasury Bond. While a yield curve inversion has been a solid indicator of a recession, it is imprecise at best. Historically, the time until a recession has varied between five and 16 months.

It is always possible that the future will be different from the past. We view the yield curve inversion as a blinking yellow light: it’s not necessary to stop but you should proceed with caution. In accordance with this, we’re watching other recession indicators to determine if the blinking yellow light may turn red.

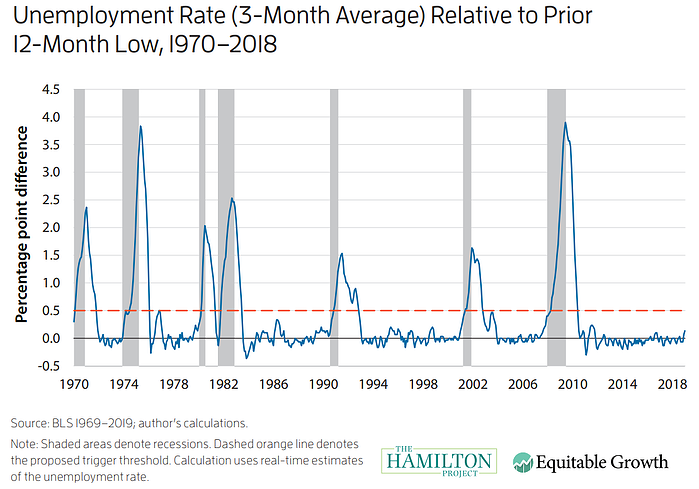

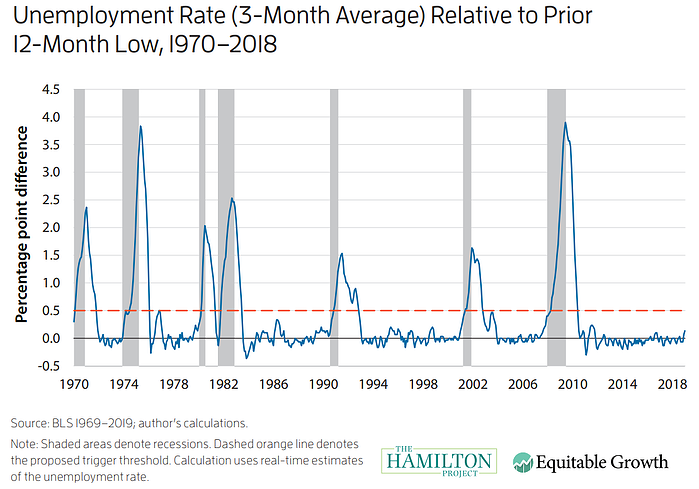

One datapoint that we watch closely for confirmation is unemployment claims. Claudia Sahm—the Section Chief for the Consumer and Community Research section in the Division of Consumer and Community Affairs at the Federal Reserve Board—recently codified this into a helpful rule, appropriately named “The Sahm Rule,” to trigger policy response at the onset of a recession. The rule’s “trigger” occurs when the 3-month average unemployment rate rises 50 basis points above its lowest point over the previous year. We intend to watch this indicator, and others like it, very closely.

Whether or not a recession occurs will likely determine the direction of the market over the next five years, but what about over a shorter time horizon? We believe the overriding question in the markets is the trade war, which coincidentally may be a large factor in whether or not the domestic and/or global economies enter a recession. Deal or no deal? The markets have become accustomed to the constant news flow, often contradictory, that comes out almost daily. Trade talk/rumors/tweets have become more of a Hasbro concoction than anything else…except it is not a game.

Globally, manufacturing (as measured by the Purchasing Managers Indices) continues to contract and all five of the world’s largest economies are in a manufacturing contraction. In the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) October update, the organization reduced its 2019 world trade growth forecast from 2.6% to 1.2%, stating “risks to the forecast are heavily weighted to the downside and dominated by trade policy.” The Director-General of the WTO, Roberto Azevêdo, summarized the situation perfectly:

“The darkening outlook for trade is discouraging but not unexpected. Beyond their direct effects, trade conflicts heighten uncertainty, which is leading some businesses to delay the productivity-enhancing investments that are essential to raising living standards.”

A trade truce will do little good unless a significant portion of the current tariffs are removed and all proposed and future tariffs are shelved. It is worth remembering that the last time tariffs were used in this fashion during the 1930’s, the Smoot-Hawley tariffs helped crater world trade by 2/3rds in just 5 or 6 years! Let’s hope this does not reoccur while at the same time recognizing the gravity of the situation.

For the sake of all economic participants, we hope that the current economic expansion continues ad infinitum, but as realists we know that trees do not grow to the sky. The future will bring good times and bad. We have relied on our quantitative systems to navigate a variety of market conditions in the past, and we will continue to do so in the future.

As always, we thank you for your confidence and for your business.